The Estonian healthcare system relies on solidarity-based health insurance, in which working-age and healthy people contribute to covering their own medical costs as well as those of other insured people. The services are centrally financed and organised by the Estonian Health Insurance Fund. Two-thirds of healthcare revenues come from social tax paid by working people, who make up about half of all those who have health insurance.

Although the working age population is decreasing, the continuous growth in employment has helped maintain this ratio (one employee for every additional person with health insurance). Currently, Estonia has one of the highest employment rates in Europe, including among those of retirement age. For example, about a third of people aged 65–74 are working.

Healthcare costs are rising rapidly in Estonia. They are currently three times higher than in 2010 and twice as high as in 2015. However, their share of GDP (7.5%) is still considerably lower than the European average (10.2%). If Estonian healthcare financing were at the EU average, there would be around 1 billion euros more in the healthcare system every year in Estonia.

Rising prices of healthcare services (51–55%) have been the main driver of the increasing expenses, with the salary growth of healthcare professionals playing the largest role. About 40% of the rising costs can be attributed to the increasing use of services.

Table. Reasons for rising healthcare costs

Source: Authors’ calculations based on TAI and Eurostat data.

The sharp increase in healthcare costs has resulted in annual expenditures exceeding revenues by as much as 100 million euros. The Estonian Health Insurance Fund has been using reserves to fill the gap, but those reserves will be depleted in about five years.

Salary increases have significantly reduced the outflow of healthcare workers, which is now almost ten times lower than in 2012. Nevertheless, the shortage of healthcare professionals remains the second major challenge for the system besides financing. For instance, the system could be short of around 700 nurses within ten years and about half of family physicians might leave their job. This concern is exacerbated by growing workload and working overtime, increasing the risk of burnout, especially in the public sector.

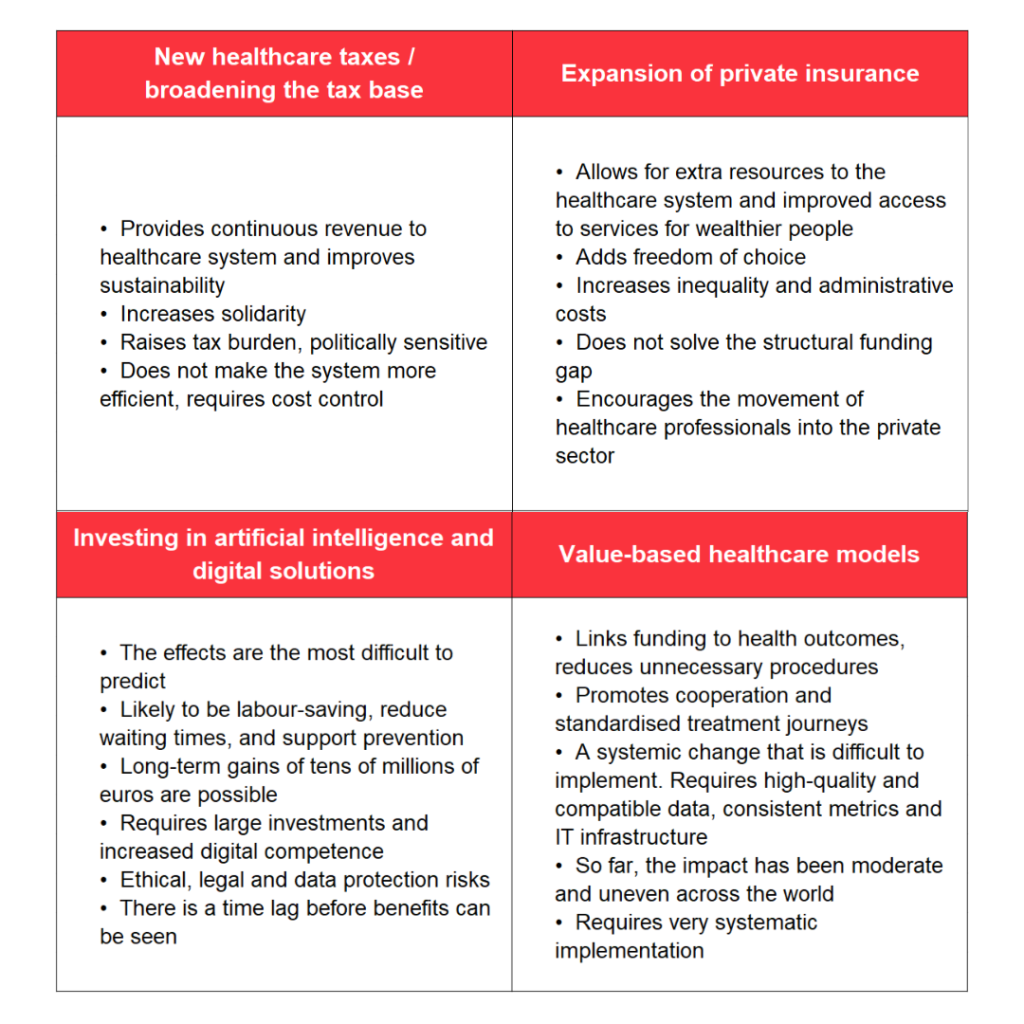

In the coming years, one of the most important issues is to figure out to what extent the labour shortage can be alleviated using technology that would help reduce the working time of healthcare workers. However, the adoption of new technologies is hindered by fragmented databases, increasingly strict interpretations of data protection rules, and healthcare professionals’ limited readiness to make use of technological opportunities. Moreover, there is a risk that heavy reliance on technology could deepen inequalities if the most vulnerable are excluded from digital services.

The healthcare system is also facing ageing infrastructure, as many buildings are older than 50 years. In recent years, infrastructure investments have grown to more than 200 million euros per year, primarily thanks to EU funds. However, in a few years’ time, it may be necessary to find new sources for healthcare infrastructure development due to the decrease in EU funding. About 65 million euros will also be needed to replace outdated IT systems, whose maintenance has become costly and poses information security risks.

However, residents of Estonia are now healthier in many key health indicators than they were decades ago. For instance, based on composite health metric DALY, 120,000 healthy years have been gained in the past 20 years, with a total monetary value of 5.7 billion euros. Despite the improvement in general health indicators, however, considerable health inequalities persist: people with lower education and income have a significantly shorter life expectancy and poorer health behaviour. There are also large regional differences. For example, residents of Hiiu County live more than ten years longer in good health than those in Võru County.

In Estonia, the payments for healthcare services are based mainly on quantity, i.e. according to the number of procedures and appointments. This encourages increasing quantity without creating incentives to improve outcomes. Value-based healthcare (VBHC) means paying for health outcomes and quality, rather than the sheer quantity of services. Around the world, testing of VBHC models is still in its infancy. The experiences of European countries in this area indicate that quality does improve, but there is no breakthrough yet in controlling the expenses. VBHC is not just a payment model, it is a broader system change that includes outcome measurement, high-quality data, a patient-centric approach, and linking funding to value created. Thus, it requires consistent political support, preparedness of healthcare institutions and healthcare professionals and seamless data exchange between parties.

Expanding private insurance as a source of additional healthcare funding is increasingly being discussed. In 2025, private insurance accounts for only 0.8% of the healthcare market in Estonia, but it is growing rapidly and already covers about one-tenth of the workforce. A study commissioned by the Foresight Centre and conducted by the University of Tartu reveals that private insurance is primarily offered by large companies that pay high average salaries, where private insurance is more likely used by highly educated people aged 25–39 with a good health assessment. Experience from European countries shows that private insurance offers more choices, but without strong regulation, it tends to deepen inequality and fails to address the structural funding gap.

There are several paths for the development of private insurance in the future of Estonian healthcare. If the current situation continues, employer-provided insurance will increase mainly in larger and higher-paying companies, offering their employees better access to healthcare services. However, since insurance companies are price takers and there is no price competition for services, the service prices will not fall. The expenses of the Health Insurance Fund are increasing due to growing competition for healthcare workers, especially in areas where workforce is scarce, which in turn creates wage pressure.

Increasing tax incentives would encourage employers to offer private health insurance more widely, but it could reduce state tax revenues if part of the wage expenses were replaced by tax-free healthcare benefits. It is also likely that better access to healthcare services would be available only to certain groups of employees.

A semi-mandatory private health insurance scheme covering co-payments is the only option explored that would inject additional funds to the system and ease the burden on the Health Insurance Fund. At the same time, there would be a growing administrative burden associated with managing and supervising an additional layer of insurance. The state would have to cover insurance premiums for lower-income residents to prevent inequality in access to healthcare services from increasing. To mitigate negative impacts, clear protection mechanisms should be established: limit the selective choice of insurers, ensure transparency and minimum standard of packages, and avoid creating price pressure on the Health Insurance Fund.

The increase in employment has so far been an important factor that has helped offset the effects of population ageing and price increases on the Health Insurance Fund’s revenues. Each percentage point increase in employment would add around 30 million euros to the Health Insurance Fund’s budget in the future as well. A considerably larger influx of foreign workforce would have an even greater impact. For example, an extra 10,000 foreign workers with an average salary would add approximately 37 million euros to the Health Insurance Fund’s budget; meanwhile, raising the retirement age by two years would add 34 million euros. However, these steps are much more controversial in society compared to increasing employment.

The report outlines three possible development paths to help understand where Estonian healthcare may be heading over the next decade.

In the “Digital Hope” scenario, Estonia would strongly invest in digital solutions, health technologies and the outcome-based transformation of payment models used in healthcare. The wins would be in the tens of millions of euros, but not in the first few years, when investments would exceed gains. Clearly defining the roles of employees and technology as well as resolving ethical issues would be the greatest challenges.

The “Market Healthcare” scenario would take the path of increasing the role of private insurance, which would initially bring extra revenue to the system and allow more solvent people to access healthcare services faster. But without increasing state contributions, doctors and nurses would go to private companies for better conditions. This would result in weaker public healthcare and growing disparities in quality and access between different population groups. In public opinion, the legitimacy of health insurance taxes would lessen if people would no longer be provided with sufficient healthcare services and they must additionally buy private insurance.

In the “Too Little, Too Late” scenario, however, informed decisions are delayed and the deepens almost unnoticed. Turbulent times in the world continue, taking attention away from supporting healthcare. Funding would remain at the current revenue base, but reserves would continue to shrink amid disputes, until the quality and availability of services would decline sharply by the end of the decade. Some efficiency-boosting changes would be made, but the escalating under-financing of the system would remain unresolved. As the problem worsens, temporary tax increases would be implemented, which would provide replenishment for the depleted reserves for three years and enable the payment of debts incurred to hospitals, but in the long run, they would simply postpone the crisis.

Across all scenarios, the key question remains: how strong should the principle of solidarity and universal access to healthcare be? It is necessary to decide whether to broaden the tax base and strengthen public funding or put more emphasis on private insurance. Another decision that needs to be made in the case of all scenarios is related to the scope and purpose of using technology: should technology be implemented primarily to fill gaps created by labour shortages, or to make healthcare professionals’ daily tasks more efficient? At the same time, issues related to equal access, ethics and data protection must also be resolved.

The report provides four possible approaches to address the healthcare funding crisis. These are presented in the table below.

An independent think tank at the Riigikogu

An independent think tank at the Riigikogu