The future of private funding in culture and sports

Culture and sports carry national identity and maintain social memory. At the same time, they create a strong sense of belonging, boost health and support social cohesion and personal well-being. Culture and sports create economic value through job creation, tourism and exports. We cannot focus only on short-term costs and revenues in funding these sectors; it is important to take a look at their long-term impact to help build a healthier, more cohesive and more economically viable society.

Estonia ranks among the top countries in Europe in terms of the proportion of public sector funding in culture and sports, but to ensure the vitality of this sector, we need a more diverse funding model, primarily an increase in private funding. The public sector may not be able to significantly increase culture and sports funding in the coming decades, as the need for finances is growing rapidly in other sectors as well, namely the social and healthcare system as well as security.

Since the 2009 financial crisis, European Union countries have reduced the state’s share in culture and sports funding, encouraging creative people and organisations to make their activities more commercial and increase private funding. Private funding can come from both companies and private individuals. This report takes a closer look at companies’ support for culture and sports.

Research literature and reports by international organisations on donations show that private funders’ goals in the culture and sports sector are rapidly changing: there is a growing emphasis on the digital visibility of the supported organisation or event, the development of long-term partnerships and on support impact assessment. We can highlight the following trends.

- Digital solutions, such as crowdfunding platforms, help the culture and sports sector collect donations more easily. However, digitalisation means that competition between organisations seeking funding is increasing.

- Donor involvement in an organisation’s activities is growing – more and more donors want a more personal connection with the organisation they support. The growing importance of personal connections means that donors want more transparency regarding how donations are used.

- The growing importance of social objectives, or strategic donating – donors aim to achieve some desired positive and sustainable social change. It is becoming more and more common for companies themselves to look for partners whose activities they wish to support.

- As donors want broader benefits for society, there is a need to measure social, political or cultural impact. This means, however, that for each object and event, it is necessary to consider which data and methods are suitable for demonstrating the impact and its various aspects, e.g. cultural, environmental, economic or social.

- The diversity of special taxations for donations is growing – in addition to tax benefits as the most common type of special taxation, other methods are emerging, such as donation amplification and tax designation schemes.

Donating and sponsoring are the most common ways for Estonian companies to support cultural and sports institutions. Besides these, free or discounted products and services are offered and in-kind donations are made, for instance in the form of volunteering.

In Estonia, the volume of donations has grown year after year at almost the same pace as the economy. Although the number of individual donors has increased over the years, it has done so more slowly than the total amount and the number of donations. This indicates that the growth in donations is mainly driven by those who have donated before and are now increasing their contributions.

The average size of donations from both private individuals and companies has grown over time. In 2023, the average private individual donor gave approximately 60 euros, or 5 euros per month, to charity. The median donation is highest among those born between 1960 and 1969 (90 euros per year) and lowest among those born after 2000 (15 euros per year). The average of companies’ donations is affected by a few large donations. The average donation is over 6000 euros, but the median donation, or the donation of the average donor, is more than ten times smaller.

The greatest potential for increasing donations comes from companies. According to the current Income Tax Act, companies can donate up to 10% of the profit of the previous financial year or 3% of the salaries paid out, income tax-free, to institutions included in the list of organisations with income tax advantages. Companies use a very small part of the possible tax-free donation volume. In 2023, a total of 16.5 million euros was donated to the institutions on the list, including 4.4 million euros in support for the culture and sports sector. It would have been possible to donate 1.1 billion euros tax-free. Companies supporting the culture and sports sector are most motivated by a sense of mission, as well as transparency in how the recipient uses the support.

A stronger donation culture and greater awareness can foster growth in private funding. For private funding to grow, it is important to cultivate a donation culture, as international studies have also indicated. More recognition of supporters as well as better visibility of culture and sports organisations could be helpful. Encouraging donations that already have existing tax benefits is one option. However, Estonian companies’ awareness of tax benefits is rather poor.

Donation matching scheme by state can influence the donation behaviour of up to 40% of companies. For Estonian companies, public sector support may feel like quality assurance that encourages them to donate. A survey by the Foresight Centre showed that 37% of companies that already support an organisation or institution would increase their donations either significantly or to some extent if the state added half a euro to every euro donated. Of the companies that have not supported an organisation or a person in the past two years, 39% would consider donating if the state boosted it. At the same time, 58% of companies already donating believe that this measure would not cause them to increase donations and 5% of companies would reduce the current volume of donations.

In order to provide analytical support for making changes to the private funding system, the Foresight Centre has developed a private funding calculator for the culture and sports sector. The calculator allows us to assess the approximate impact of some proposals made for increasing private funding on the volume of private funds received in the sports and culture sector and on state revenue and expenditure.

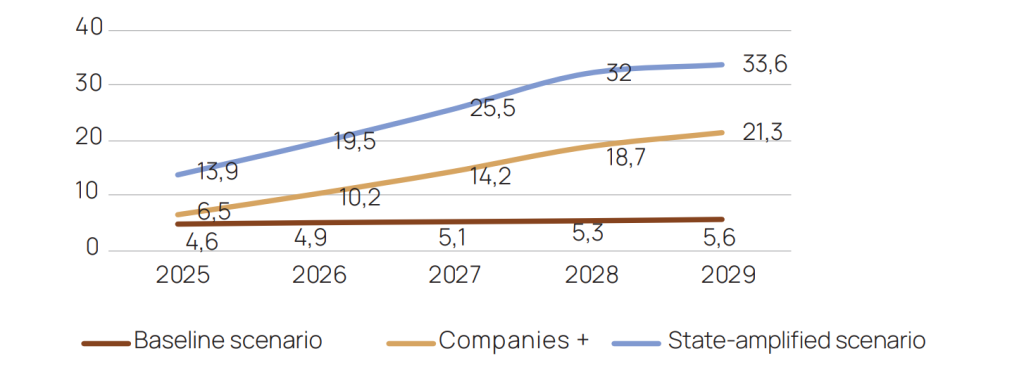

The report examines three scenarios. The first scenario reflects the continuation of current trends, the second scenario envisions the Estonian companies’ donation culture becoming more like that of Scandinavian countries and the third scenario encourages companies to donate through an additional contribution from the state. From the perspective of the donation recipients, the most profitable scenario, given the assumptions made, is the one in which the state tops up companies’ donations. This scheme would generate approximately 14 million euros in donations in the first year of its implementation, an increase of over 9 million euros compared to the baseline scenario. The additional revenue would grow in each consecutive year. At the same time, amplifying private sector donations is an expense for the state.

Figure 1. Donation recipients’ income in millions of euros

Source: Foresight Centre, 2025

On the other hand, stimulating the culture and sports sector has an energising effect on the economy – part of the state’s expenses are immediately covered by tax revenue generated from the use of donations. Also, the increased activity of institutions that have received support increases gross domestic product, because the organisations that have received donations use products and services from other sectors of the economy as well. A state investment of 15 million euros would return 10 million euros in tax revenue and 63.5 million euros in gross domestic product in 2035 under these assumptions. Engaging in recreational, sports and cultural activities can help people stay in the labour market for longer and maintain an active lifestyle. This would be very helpful in alleviating labour shortages and reducing the need for foreign labour besides additional tax revenue.

A tax received on remote gambling could bring additional income to finance culture and sports. The money collected from the tax on gambling is used to support culture and sports through the Cultural Endowment currently as well. Revenues from gambling tax have grown rapidly. However, tax revenue from gaming halls has decreased, while the tax revenue from online gambling has increased sharply, as in 2019, it accounted for only a tenth of total gambling tax revenue, whereas in 2024, it constituted more than a third of total gambling tax revenue. Estonia’s liberal legal environment, which allows companies to operate internationally, has facilitated the rapid growth of the remote gambling industry. A more optimistic forecast indicates that according to a simulation based on market participants’ estimates, tax revenue from remote gambling could multiply by 2029. Utilising this potential requires, on the one hand, for the state’s capacity in procedural actions to increase, and on the other hand, it is important to maintain an attractive tax rate compared to other countries. This extra money would allow the state to boost companies’ donations and implement development plans for cultural and sports facilities.

An independent think tank at the Riigikogu

An independent think tank at the Riigikogu